C++ Reflection

June 16, 2016

Preface

I set out this summer (2015) to implement a flexible reflection system for the game project I’m working on. This repository contains a skeleton for parts of the system that I prototyped throughout the summer. With the proper dependencies and build system setup, you should have enough to integrate into your engine / application without much fuss.

Quick Intro

As a statically typed language, C++ wasn’t designed to facilitate runtime type information. Instead, it’s crazy fast and optimization friendly. Games are performance critical applications - it is for this reason that C++ is basically the standard backend.

Type introspection is crucial for complex / large code bases that need to interface with tools (i.e. a game editor). Unless you’re a team of all programmers (I’m sorry if that’s the case) it is effectively impossible to iterate upon a larger game without some set of tools to abstract away code (especially in 3D). Without type introspection, you can expect to copy and paste a lot of boilerplate code. This is absurdly tedious and undesirable.

The good news is that there are tons and tons of great resources out there for “extending” C++ to include meta information within your code base. The most common approaches you’ll find are as follows:

- Using macros and templates to simplify the craziness that is writing the aforementioned boilerplate code.

- Parsing your code to generate the crazy boilerplate code.

The latter technique isn’t adopted nearly as much as the former, but feels like it’s becoming much more common. With that said, I chose to use the generation technique. I’m pretty glad I did.

The purpose of this repository is to be a simple jumpstart reference for those interested in implementing the generation method in their own code base.

Here are a few links that cover more specifics on the concept (specifically in the realm of C/C++)

- GDC: Physics for Game Programmers - Debugging (it’s relevant, I swear!)

- GDC: Robustification Through Introspection and Analysis Tools (Avoiding Developer Taxes)

- Game Engine Metadata Creation with Clang

- Parsing C++ in Python with Clang

Goals

Make the pipeline as hands off as possible.

Specifically, you shouldn’t have to jump through a bunch of hoops just to expose your code to the reflection runtime library. Make changes to your code, recompile, and the changes are reflected immediately (yep, it was intended).

No extra button clicks or steps to synchronize the reflection data.

Provide rich functionality in the runtime library.

If we’re going through all this trouble in the first place, might as well make it worth while!

Avoid huge build times.

We’re effectively compiling our code twice. First to parse our code base and understand it as intricately as a compiler does, then to actually compile it as per usual (with the addition of our generated source).

This is one of the downsides to the generation approach. Instead of manually writing these macros inline with our source, we’re using the brains of a compiler. However, we would much rather sacrifice a little bit shorter build times for the luxury of cleaner, less cluttered code.

Unfortunately, this also implies creating a much less intuitive build pipeline. Don’t worry though! I have some nifty diagrams for you.

Pipeline

In our engine (we call it Ursine Engine, because we’re dangerously clever and played on the fact that our team name is Bear King), we use CMake for managing most aspects of the overall build pipeline. CMake is a horribly wonderful tool that I’ve come to love despite hating it at the same time. It allows us to generate solutions for most IDEs that anyone on the team likes to use, although currently, everyone is using Visual Studio 2015 (finally some C++14, baby!).

CMake makes this pipeline surprisingly simple which was a relief. I won’t go into much specific detail, but I’ll provide relevant snippets of the integration into our engine a little later when I describe the code in this repository.

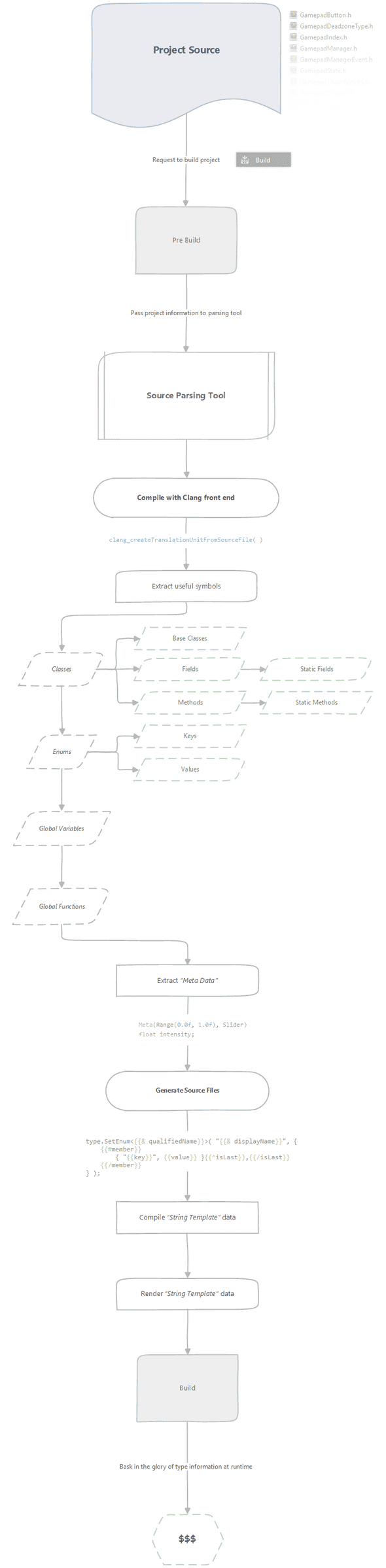

Here’s a diagram of the entire pipeline from writing the source, to building your game / application.

Code

The repository has two parts - Parser and Runtime.

- Parser is for the command line source parsing tool. (requires Boost 1.59.0 and libclang 3.7.0)

- Runtime is for the reflection runtime library.

CMake Prebuild Example

This is basic example of adding the prebuild step to an existing target in CMake.

set(PROJECT_NAME "Example")

# assume this contains header files for this project

set(PROJECT_HEADER_FILES ...)

# assume this contains source files for this project

set(PROJECT_SOURCE_FILES ...)

# generated file names, in the build directory

set(META_GENERATED_HEADER "${CMAKE_CURRENT_BINARY_DIR}/Meta.Generated.h")

set(META_GENERATED_SOURCE "${CMAKE_CURRENT_BINARY_DIR}/Meta.Generated.cpp")

# create the project target

add_executable(${PROJECT_NAME}

${PROJECT_HEADER_FILES}

${PROJECT_SOURCE_FILES}

# make sure the generated header and source are included

${META_GENERATED_HEADER}

${META_GENERATED_SOURCE}

)

# path to the reflection parser executable

set(PARSE_TOOL_EXE "ReflectionParser.exe")

# input source file to pass to the reflection parser compiler

# in this file, include any files that you want exposed to the parser

set(PROJECT_META_HEADER "Reflection.h")

# fetch all include directories for the project target

get_property(DIRECTORIES TARGET ${PROJECT_NAME} PROPERTY INCLUDE_DIRECTORIES)

# flags that will eventually be based to the reflection parser compiler

set(META_FLAGS "")

# build the include directory flags

foreach (DIRECTORY ${DIRECTORIES})

set(META_FLAGS ${meta_flags} "\\\\-I${DIRECTORY}")

endforeach ()

# include the system directories

if (MSVC)

# assume ${VS_VERSION} is the version of Visual Studio being used to compile

set(META_FLAGS ${META_FLAGS}

"\\\\-IC:/Program Files (x86)/Microsoft Visual Studio ${VS_VERSION}/VC/include"

)

else ()

# you can figure it out for other compilers :)

message(FATAL_ERROR "System include directories not implemented for this compiler.")

endif ()

# add the command that invokes the reflection parser executable

# whenever a header file in your project has changed

add_custom_command(

OUTPUT ${META_GENERATED_HEADER} ${META_GENERATED_SOURCE}

DEPENDS ${PROJECT_HEADER_FILES}

COMMAND call "${PARSE_TOOL_EXE}"

--target-name "${PROJECT_NAME}"

--in-source "${CMAKE_CURRENT_SOURCE_DIR}/${PROJECT_SOURCE_DIR}/${PROJECT_META_HEADER}"

--out-header "${META_GENERATED_HEADER}"

--out-source "${META_GENERATED_SOURCE}"

--flags ${META_FLAGS}

)String Templates

Generating code is usually a pretty ugly process.

Instead of writing the characters manually (i.e. output += "REGISTER_FUNCTION(" + name + ")" ), I wanted to use “String Templates”. That is why I chose Mustache. I found a simple header only implemenation, which is included in the Parser section.

In the Generate Source Files section of the pipeline diagram, you’ll notice two steps. “Compile” and “Render”. Compile simply takes all of the types that we’ve extracted and compiles the data to be referenced in Mustache. Render actually renders the templates and writes them to the configured output files.

In the Templates folder of the repository, you’ll find the mustache template files referenced in the reflection parser.

Type Meta Data

One of the biggest features that I wanted to implement in the runtime library is being able to add meta data to types at compile time.

If you’ve ever used C#, you know they have a pretty groovy reflection system built into the language. I really like their syntax for Attributes, which is a way to add meta data to language types / constructs.

The closest I could get to this style, was with the use of Macros. C++11 introduced Attribute Specifiers as a way to hint compilers on intended behavior or add language extensions. Unfortunately, compiler support varies widely, and as mentioned it’s only managed at compile time.

Luckily for us, Clang supports the attribute annotate( ). You can extract the contents of an annotation with libclang.

The syntax for this attribute look something like this.

__attribute__(( annotate( "Hey look at this annotation!" ) ))You might be thinking, “But it’s only for Clang.. how will this work in MSVC?”

More good news! libclang preprocesses source files, so we can use preprocessor directives. In the source parsing tool, I define __REFLECTION_PARSER__ before compiling. We can use this to make a nice solution for all compilers.

#if defined(__REFLECTION_PARSER__)

# define Meta(...) __attribute__((annotate(#__VA_ARGS__)))

#else

# define Meta(...)

#endifWe would use it like so.

Meta(Mashed)

int potatoes;Now that I could annotate code, I needed to define how I would interact with it. Initially I assumed key value pairs separated by commas, like so.

Meta(Key = Value, Key2, Key = "Yep!")But after reviewing this approach with my teammate Jordan, he came up with the brilliant idea of doing exactly what C# does, and that is using user defined types as annotations, queryable at runtime. So I came up with this.

struct Mashed : public MetaProperty { };

Meta(Mashed)

int potatoes;Here’s how it works - I treat all values delimited by commas as constructors. If a value doesn’t have parentheses, it’s assumed to be a default constructor.

For each constructor, I then extract the arguments provided. When I generate the source, I simply paste the extracted arguments as a constructor call of the provided type. The value is converted to a Variant and accessible at runtime. This allows us to do some really awesome things.

enum class SliderType

{

Horizontal,

Vertical

};

struct Slider : public MetaProperty

{

SliderType type;

Slider(SliderType type)

: type(type) { }

};

struct Range : public MetaProperty

{

float min, max;

Range(float min, float max)

: min(min)

, max(max) { }

};

Meta(Range(0.0f, 1.0f), Slider(SliderType::Horizontal))

float someIntensityField;One of the coolest things about this, aside from type safety, is that Visual Studio correctly syntax highlights the contents of the macro and also provides intellisense! It’s a beautiful thing. Here’s a more complete example of interfacing with it at runtime using the runtime library.

struct SoundEffect

{

Meta(Range(0.0f, 100.0f))

float volume;

};

int main(void)

{

// you can also use type meta::Type::Get( "SoundEffect" ) based on a string name

Type soundEffectType = typeof( SoundEffect );

// the volume field in the SoundEffect struct

Field volumeField = soundEffectType.GetField( "volume" );

// meta data for the volume field

MetaManager &volumeMeta = volumeField.GetMeta( );

// getting the "Range" property, then casting the variant as a range

Range volumeRange = volumeMeta.GetProperty( typeof( Range ) ).GetValue( );

// 0.0f

float min = volumeRange.min;

// 100.0f

float max = volumeRange.max;

return 0;

}Function Binding

Another notoriously difficult or convoluted process in managing reflection info in C++ is dynamically invoking functions / methods.

The most common approach is to store raw function / method pointers and calculate the offsets of arguments. The result is a ton of templates and difficult to follow operations. Not to mention, I can’t imagine it’s fun to debug!

In libclang, you’re able to easily extract signatures from functions. With this in mind, I came up with the most simple approach that I could think of. Wrapping function calls in generated lambdas.

Here’s a simple demonstration of the concept.

int foo(int a, float b, double c)

{

return 0;

}

auto fooWrapper = [](int a, float b, double c)

{

return foo(a, b, c);

};

// same behavior as foo(0, 1.0f, 2.0);

fooWrapper(0, 1.0f, 2.0);In the context of our runtime library, here’s an example of something that might be generated for a class method.

class DemoClass

{

public:

int someMethod(int a)

{

return a;

}

};

auto someMethodWrapper = [](Variant &obj, ArgumentList &args)

{

auto &instance = obj.GetValue( );

return Variant {

instance.someMethod(

args[ 0 ].GetValue( )

)

};

};That’s it! It’s much less complicated than the previously mentioned approach. This concept is also applied to fields / globals with their getters and setters.

There are some downsides though:

- Larger code size. For each generated lambda, the compiler has to generate a bunch of symbols behind the scenes.

- Larger compile times.

- Decent amount of indirection just for one function call.

You shouldn’t have to worry too much however. If like most people, you use reflection for editor functionality, not a physics simulation. Performance in most cases is not critical.

Here’s a more complete example of dynamically calling functions with the runtime library.

struct SoundEffect

{

float volume;

void Load(const std::string &filename);

};

int main(void)

{

Type soundEffectType = typeof( SoundEffect );

Field volumeField = soundEffectType.GetField( "volume" );

// the runtime supports overloading, but by default returns the first overload

Method loadMethod = soundEffectType.GetMethod( "Load" );

// creates an instance of a sound effect

Variant effect = soundEffectType.Create( );

// effect.volume is now 85

volumeField.SetValue( effect, 85.0f );

// 85

volumeField.GetValue( effect );

// effect.Load is called

loadMethod.Invoke( effect, std::string { "Explosion.wav" } );

return 0;

}